Amplifying Black Advocate Voices: How Bias Has Affected My Patient Journey

Being diagnosed with an autoimmune condition like lupus can take years. Many people report their early symptoms were dismissed by doctors or they were misdiagnosed. This delays treatment, which lets complications grow worse.

This is even more true for people of color. The National Healthcare Disparities Report showed dark-skinned people receive lower-quality care than white people. This large study found health care professionals were generally positive about white people and negative about people of color.1

For Black History Month, we highlight the journeys of Black advocates in our rheumatic communities:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- psoriatic arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Axial spondyloarthritis

- Lupus

We asked: How has race affected your patient journey? Were you ever dismissed, not listened to, ignored, or did not feel represented? We hope these stories give our readers insight into the added burden faced by people of color with autoimmune conditions.

How has race affected your patient journey?

"I definitely feel that my race has impacted the way doctors took me seriously at the beginning of my journey of being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. I was between the ages of 10 and 16 when my mom and I were on the journey of trying to find an answer for my pain, and time and time again we kept being dismissed by doctors. They did not take me seriously one bit, and once my mom came in to vouch for me, they completely dismissed her as well. One doctor told me, 'Are you sure you correctly know what it means to be in pain?' When I was only a child, I simply thought to myself, 'Well, of course, I know what it means,' because I didn’t know that the doctor was viewing me as someone who would lie or not understand 'true' pain based on the color of my skin." - Randi, RheumatoidArthritis.net Advocate

"I definitely feel that my race has impacted the way doctors took me seriously at the beginning of my journey of being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. I was between the ages of 10 and 16 when my mom and I were on the journey of trying to find an answer for my pain, and time and time again we kept being dismissed by doctors. They did not take me seriously one bit, and once my mom came in to vouch for me, they completely dismissed her as well. One doctor told me, 'Are you sure you correctly know what it means to be in pain?' When I was only a child, I simply thought to myself, 'Well, of course, I know what it means,' because I didn’t know that the doctor was viewing me as someone who would lie or not understand 'true' pain based on the color of my skin." - Randi, RheumatoidArthritis.net Advocate

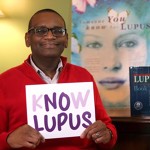

"I met with a white orthopedic physician's assistant in 2019 about tendinitis in my shoulder. She prescribed a steroid injection but first asked me if I had 'sugar,' as if I am an uneducated, simple-minded Black man who did not know that the disease is called diabetes. I have not heard a reference to 'sugar' since the 1980s. In another instance, I went to a university clinic without insurance. I did not have insurance during a portion of the 1990s. Most doctors at this clinic saw me for free thanks to my specialist. During one visit, the white receptionist yelled to the more than 10 registration agents and everyone in the large waiting room that I did not have insurance and would need to pay upfront. My mother, who worked for the same university and hospital, and I were appalled by the statement." - Christopher, Lupus.net Advocate

"I met with a white orthopedic physician's assistant in 2019 about tendinitis in my shoulder. She prescribed a steroid injection but first asked me if I had 'sugar,' as if I am an uneducated, simple-minded Black man who did not know that the disease is called diabetes. I have not heard a reference to 'sugar' since the 1980s. In another instance, I went to a university clinic without insurance. I did not have insurance during a portion of the 1990s. Most doctors at this clinic saw me for free thanks to my specialist. During one visit, the white receptionist yelled to the more than 10 registration agents and everyone in the large waiting room that I did not have insurance and would need to pay upfront. My mother, who worked for the same university and hospital, and I were appalled by the statement." - Christopher, Lupus.net Advocate

"I was a guinea pig for more than 30 years. I could tell you some stories that would make your hair stand straight up on your head. I have been seeing a doctor since the age of 5 every month of my life. The worst part for me was finding a doctor who knew how to treat Black skin, and being a woman didn't help. I was always covered head-to-toe with psoriasis, but doctors would give me a small tube of cream for my whole body. I said something to a doctor about this once, and he told me to add Vaseline to it to make it last. If I said I was in pain, I was told it was all in my head and to take an aspirin. I lost count years ago of how many times I could barely walk into a doctor's office in tears because my psoriasis had fused together, which caused me great pain. Doctors never saw me – they only saw my Black skin." - Diane, Psoriatic-Arthritis.com Advocate

"I was a guinea pig for more than 30 years. I could tell you some stories that would make your hair stand straight up on your head. I have been seeing a doctor since the age of 5 every month of my life. The worst part for me was finding a doctor who knew how to treat Black skin, and being a woman didn't help. I was always covered head-to-toe with psoriasis, but doctors would give me a small tube of cream for my whole body. I said something to a doctor about this once, and he told me to add Vaseline to it to make it last. If I said I was in pain, I was told it was all in my head and to take an aspirin. I lost count years ago of how many times I could barely walk into a doctor's office in tears because my psoriasis had fused together, which caused me great pain. Doctors never saw me – they only saw my Black skin." - Diane, Psoriatic-Arthritis.com Advocate

"In general, I often feel dismissed. It's assumed, especially during hospitalizations, that I'm not knowledgeable about my own health, i.e. pill dosage, dialysis prescription, etc. It isn't until my nurse or doctor sees documentation or is proven wrong that they start to listen. I do remember one hospitalization where I had excruciating pain, the worse pain I've ever felt, that turned out to be pancreatitis. The initial dose of medicine I was given in the ER didn't touch the pain. I found myself in mind-numbing pain, but the second dose of medication was significantly delayed. I can't help thinking they thought I could 'handle' the pain because of the myth that Black patients have higher pain tolerance." - Gabrielle, Lupus.net Advocate

"In general, I often feel dismissed. It's assumed, especially during hospitalizations, that I'm not knowledgeable about my own health, i.e. pill dosage, dialysis prescription, etc. It isn't until my nurse or doctor sees documentation or is proven wrong that they start to listen. I do remember one hospitalization where I had excruciating pain, the worse pain I've ever felt, that turned out to be pancreatitis. The initial dose of medicine I was given in the ER didn't touch the pain. I found myself in mind-numbing pain, but the second dose of medication was significantly delayed. I can't help thinking they thought I could 'handle' the pain because of the myth that Black patients have higher pain tolerance." - Gabrielle, Lupus.net Advocate

"Race affects every part of my life with spondyloarthritis. Many Americans are invested in racial essentialism, which is the belief that race is an inherited biological reality that defines who we are. To clinicians, researchers, and patients, spondyloarthritis and other associated disorders like psoriasis are generally seen as impacting white people.2

"Race affects every part of my life with spondyloarthritis. Many Americans are invested in racial essentialism, which is the belief that race is an inherited biological reality that defines who we are. To clinicians, researchers, and patients, spondyloarthritis and other associated disorders like psoriasis are generally seen as impacting white people.2

Our nation's history forms our thinking in binary terms: a person is one or another. The idea that African Americans or others of African descent might share some genetic traits with the established base of patients is trampled under all of this. And there is little research targeting 'new' disease pathways in our communities. This means there are few patients, few research participants, and continued artificial validation of the notion of racialized disease." - Dawn, AnkylosingSpondylitis.net

"According to the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF), psoriasis affects only 1.3 percent of African Americans and 2.5 percent of white people. I often wonder if this number is skewed due to the lack of psoriasis research for darker-complexion skin. I had my first flare at 7 years old, and although I was immediately diagnosed with psoriasis, I cannot say that continued to be the case throughout my journey.

"According to the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF), psoriasis affects only 1.3 percent of African Americans and 2.5 percent of white people. I often wonder if this number is skewed due to the lack of psoriasis research for darker-complexion skin. I had my first flare at 7 years old, and although I was immediately diagnosed with psoriasis, I cannot say that continued to be the case throughout my journey.

Through the years, I have been told I could have other conditions, such as a fungus of the skin or other diseases hard to pronounce. One of the reasons for my misdiagnoses is the fact my disease does not present like what's described in the medical textbooks as psoriasis. If you Google the term, psoriasis you will find hundreds of images displaying red, flaky, thick patches of inflamed skin on white bodies. Not a single photo shows a person of deep complexion living with the disease. For me, this is disheartening.

This lack of representation negatively impacts the patient experience for people of color living with this disease, including myself, in a few ways. First doctors, particularly primary physicians (which are typically the first doctor you will see with your first flare), are more likely to misdiagnose a Black patient because the disease in dark skin does not present itself as the textbook definition. In many cases, psoriasis in a Black person will be brown, deep purple, red, and pink. A misdiagnosis will lead to ineffective treatments, which will not be sufficient, increasing the patient's risk to factors, such as side effects that have no reward.

Additionally, this lack of representation is present in TV commercials and print ads, furthering stigmatizing psoriasis for Black people like myself. There have been times I have shared with people that I have psoriasis, and they looked at me shocked and stated they didn't know Black people could get the disease. This lack of awareness is more enormous due to the lack of Black voices to speak out about the disease and lack of representation in the media, as I stated earlier. This is a problem in the medical community as a whole.

I remember sitting in a research symposium to observe a patient panel for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), another autoimmune disease that affects the skin. This disease disproportionately affects African Americans. There were 6 patients there to talk about their experience with HS, and not a single person on the panel was black. This continues to be a significant problem that needs to be better addressed by our medical leaders." - Alisha, Psoriatic-Arthritis.com Advocate

Join the conversation